So, what is bunching?

Here I will explain the basic concepts of bunching as a causal inference method. The data provided here is constructed in R for the sake of example. You can check the full code here

The Naive Approach

Imagine that you are interested in the causal effect of smoking on birth weights. Say you observe a covariate, mom’s education, and you are willing to control for that.

Okay, that sounds good. Perhaps people with more education are more inclined to not smoke, better healthcare and etc. For simplicity, you could impose a linear model, which makes the expression:

\[y_i = \beta X_i + \gamma Z_i + \varepsilon_i\]Where $y_i$ is the birth weight of baby $i$, $X_i$ is your explanatory variable, number of cigarettes smoked by baby $i$’s mom, and $Z_i$ is the mom’s education. $\varepsilon_i$ is a random shock following a normal distribution where $\mathbb{E}(\varepsilon | X, Z) = 0$.

Say you have these variables in R in a pretty neat dataset, so you run the regression and, excited, promptly shows the results to your advisor:

r$> # naive regression

naive_model <- lm(bw ~ cigs + educ)

summary(naive_model)

Call:

lm(formula = bw ~ cigs + educ)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-535.15 -124.99 -11.07 122.14 530.21

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 3024.5512 26.5450 113.941 <2e-16 ***

cigs -39.2510 0.8716 -45.035 <2e-16 ***

educ -0.7493 1.7104 -0.438 0.661

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 177.8 on 997 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.6788, Adjusted R-squared: 0.6781

F-statistic: 1053 on 2 and 997 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

bw is the birthweight, measured in grams. You have the average number of cigarettes smoked by the mom in cigs, and her education level in educ.

Do you notice something weird about this regression? Can you say that for every cigarette smoked per day, the baby loses about 40 grams when they are born?

Probably Not!

This is why it is important to always have economic intuition as your sanity check.

The hint, and this is where your advisor would point out, lies on the educ coefficient. -0.7? That seems off, right? It implies babies are worse off as we increase the mom’s education level.

What is happening here then?

The problem relies on what we do not observe in the data. What if there is a variable, unobserved $\eta$ in which influences not only directly birth weights, but also the propensity to smoke?

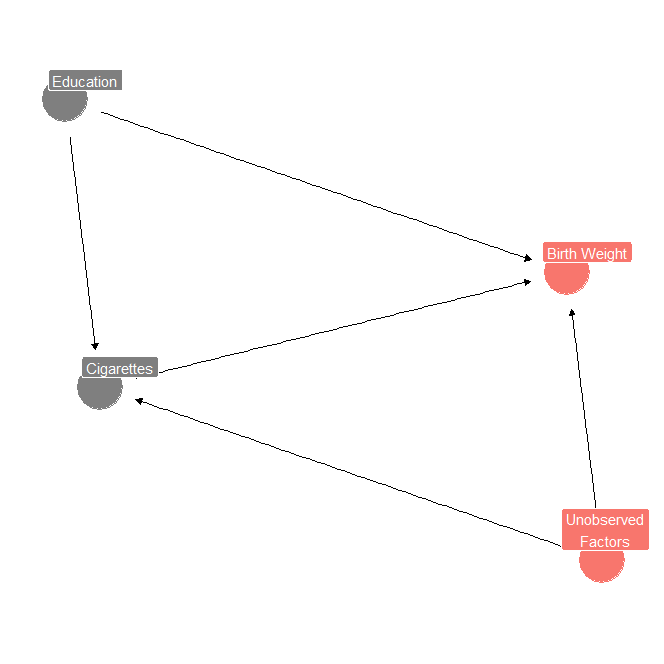

Let us make a pretty DAG representing this using the awesome package ggdag:

# Making cool DAGs with ggdag

library(tidyverse)

library(ggdag)

# Create the DAG

dag <- dagify(

bw ~ cigs + educ + eta,

cigs ~ educ + eta,

labels = c(

"bw" = "Birth Weight",

"cigs" = "Cigarettes",

"educ" = "Education",

"eta" = "Unobserved\nFactors"

),

exposure = "cigs",

outcome = "bw"

)

# Create a prettier plot

X11()

ggdag_dseparated(dag, "eta", text = FALSE, use_labels = "label") +

theme_dag_blank()+

theme(legend.position = "none")

I use the dseparated function to highlight the confounder path. It looks like this:

Notice there are 3 causal path to birth weights. The first is a direct path from education, another direct path from this $\eta$ variable, and another one, where cigarettes act as a mediator variable.

If that is the case, not only we are assuming erroneously the causal relationship between cigs and birth weights, we are probably messing with the education causal path.

So how to solve this problem? This is where bunching comes into play.

The key assumption here is that there is a proxy path between smoking cigarettes and covariates. Let us say that individuals have a propensity to smoke, like an utility function. Some individuals maximize this utility by smoking large quantities of cigarettes. Other individuals, however, are very aversed to cigarettes. They find it very repulsive in such way that they would pay not to smoke, if that was the case. There are also the marginally propensed to smoke. These moms would smoke given a chance, but they are slightly better off not smoking.

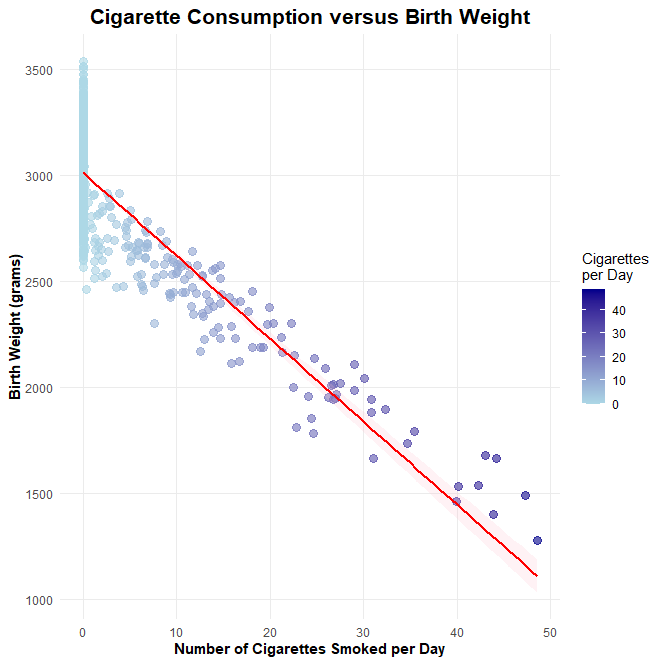

The implication of this assumption is interesting because we partially observe this mechanism. That is, we only observe individuals that are positively inclined to smoke! There is absolutely no way we can see individuals smoking negative numbers of cigarettes. However, what happens if we plot the relationship between cigarettes and birth weights?

data <- data.frame(cigs = cigs, bw = round(bw, 0))

ggplot(data, aes(x = cigs, y = bw)) +

geom_point(aes(color = cigs), alpha = 0.6, size = 3) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", color = "red", fill = "pink", alpha = 0.2) +

scale_color_gradient(low = "lightblue", high = "darkblue") +

labs(title = "Cigarette Consumption versus Birth Weight",

x = "Number of Cigarettes Smoked per Day",

y = "Birth Weight (grams)",

color = "Cigarettes\nper Day") +

theme_minimal() +

theme(

plot.title = element_text(face = "bold", size = 16, hjust = 0.5),

axis.title = element_text(face = "bold"),

legend.position = "right",

panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "white", color = NA),

plot.background = element_rect(fill = "white", color = NA)

)

I am rounding the birth weight to be integer in grams (remember this is a simulated data!) I am beautifying the plot so we can have a nice time observing it:

What is catching your eyes? Notice that this is a pretty linear relationship, until it is not: as soon as we reach 0 cigarettes, we observe a bunching pattern of birth weights.

The right question here is “why are there so many data points accumulated at the zero cigarettes?” This is the puzzle we must solve.

The answer is: there is a variable, that we do not observe, that “runs” in that relationship continuously and accepts negative values of cigarettes. This variable is affected by both observables (the education of the mom) and the unobservables ($\eta$). Therefore, if we could capture this variable, we could isolate the relationship between cigarettes and birth weights without the confounding $\eta$ factor.

Going back to metrics language:

\[X = max (0, X^*)\]That is, $X$, the observed variable representing average cigarettes per day is in fact a proxy for $X^*$, the running variable that is continuous in zero and can assume negative values (of course you may say cigarettes is an integer and therefore, not necessarily continuous. Let us abstract from this for the sake of simplicity, since it does not impose loss of generality in understanding the concept).

Recovering $X^*$ can be quite complex. However, if we are to assume a normal relationship (that is, linear) in our model, things become easier:

\[Y = \beta X + \gamma Z + \delta \eta + \varepsilon\] \[X^* = Z'\pi + \eta\]That is, the running variable of cigarettes is a linear relationship between the observable variable mom education and the unobservable variable $\eta$. Smoking is also a linear relationship, however this time we acknoledge the unobservable confounder.

So our objective is to recover this $X^*$ and use it as a proxy for $\eta$. If we can do it, we bypass the confoundness generated by unobservables.

After that, we can exogenously capture the relationship between $Y$ and $X$. If you combine the last three equations and do some math (using matrix notation now), you reach:

\[\mathbb{E}(Y\|X,Z) = X\beta + Z'(\gamma - \pi \delta) + \delta(X + \mathbb{E}(X^* \| X^* <= 0, Z)\mathbb{1}(X = 0))\]It seems complicated, but the trick is that we imput $\mathbb{E}(X^* | X^* <= 0, Z)\mathbb{1}(X = 0)$ as a proxy for when X becomes 0, meaning we now “observe” negative values for smoking cigarettes.

What is that actually doing? It is actually accounting for the unobservable which confounds our causal path.

Since our data is censored at zero and we assume linearity, we can recover this component using a tobit model. This is straightforward in R:

library(AER)

# Fit Tobit model

tobit_model <- tobit(cigs ~ educ, left = 0)

summary(tobit_model)

cigs_imput <- ifelse(cigs == 0, predict(tobit_model), cigs)

r$> # Fit Tobit model

tobit_model <- tobit(cigs ~ educ, left = 0)

summary(tobit_model)

Call:

tobit(formula = cigs ~ educ, left = 0)

Observations:

Total Left-censored Uncensored Right-censored

1000 823 177 0

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 11.26792 4.17462 2.699 0.00695 **

educ -2.20861 0.31065 -7.110 1.16e-12 ***

Log(scale) 3.08961 0.06276 49.233 < 2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

The fitted tobit model tell us that increasing education by one level decreases cigarette consumption by around 2.2. This is good enough since the model I constructed assumes this relationship to be 2. The noise comes from the fact that 80 percent of the data do not smoke. Still, it is a good approximation given the standard error.

Notice that I also made the cigs_imput variable. The remaining task is to fit the full linear model:

# Fit linear model

lm_model <- lm(bw ~ cigs + cigs_imput + educ)

r$> summary(lm_model)

Call:

lm(formula = bw ~ cigs + educ + cigs_imput)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-470.22 -118.78 -3.42 111.13 505.48

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 3124.4780 26.1223 119.61 <2e-16 ***

cigs -20.5694 1.7417 -11.81 <2e-16 ***

educ -22.0509 2.3737 -9.29 <2e-16 ***

cigs_imput -10.8197 0.8918 -12.13 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 166.1 on 996 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.7201, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7193

F-statistic: 854.2 on 3 and 996 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

The original $\beta$ value for the constructed data is $-20$. That is fantastically close! And almost half in magnitude of the predicted naive OLS. Meaning the imputation method successfully managed to remove endogeneity from average smoked cigarettes per day.

That is cool but… where is randomness?

Causal experiments usually rely on random shocks or exogenous “manipulation” that is as good as random to build their identification strategy. But in this case, there is no randomness, right? Individuals bunched at zero simply because they can’t smoke less than zero. Their propensity to smoke is hardwired in their utility function.

I think the correct way to ponder over this question is to understand why we require randomness in the first place. We need randomness in causal experiments to make sure unobservables are not affecting the treatment effect. In bunching, we exploit the bunched values to reach the unobservable confounder and ultimately control for that.

Some final notes

Bunching can definitely increase in complexity. As you are probably guessing by now, we don’t need to assume normality or a linear model. We don’t even need to impose parametrization! For a deeper overview of the method, I suggest reading Bertanha, et al. (2024)