Expectation Maximization Algorithm and Gaussian Mixtures

The EM algorithm is a powerful iterative method for finding maximum likelihood estimates in statistical models with “latent variables” or missing data. It was first proposed by Dempster, Laird, and Rubin, 1977, and since then it is a common tool in machine learning models.

Actually, it is simple, but tricky. The core idea is to iteratively alternate between two steps until it converges.

- Expectation (E) step: Estimate the missing data given the observed data and current parameter estimates.

- Maximization (M) step: Update the parameters to maximize the likelihood, treating the estimated missing data as if it were observed.

Eventually (hopefully) the algorithm converges. This is particularlly useful for Gaussian mixture models.

Say we observe a labor market data with logarithm wages and we suspect it actually is composed of two types of workers: low types, and high types. However, we don’t observe the worker type, we only observe the social identifier and their payment. Assume just one firm with a constant rent-sharing policy, that is, no matter the type or the worker, their wage in expectation is simply the average value of their types.

This concept of discrete worker types is not too far away from reality. Individuals are constantly accumulating human capital, either through school or work experience. You can think of this concept as broad categories of human capital accumulation.

Let us construct this labor market:

# Generate sample data

set.seed(123)

n <- 10000

true_means <- c(2, 3)

true_sds <- c(0.5, 0.5)

true_weights <- c(0.6, 0.4)

lmarket <- tibble(

worker_id = 1:n,

type = c(rep(1, n * true_weights[1]), rep(2, n * true_weights[2])),

log_wage = c(rnorm(n * true_weights[1], true_means[1], true_sds[1]),

rnorm(n * true_weights[2], true_means[2], true_sds[2]))

) %>%

mutate(

log_wage = log_wage - min(log_wage) + 1

)

Here I generated 10000 workers. Everytime a worker is hired, they draw their payment from a random log-normal distribution.

Because I want strictly positive log wages, after the draw, I subtract the minimal observed wage and add one unit to all observations’ wage. This will distort the moments, so let us recheck the Gaussians’ means and variances.

r$> mean(lmarket$log_wage[lmarket$type == 1])

[1] 2.633711

r$> mean(lmarket$log_wage[lmarket$type == 2])

[1] 3.624156

r$> sd(lmarket$log_wage[lmarket$type == 1])

[1] 0.4969792

r$> sd(lmarket$log_wage[lmarket$type == 2])

[1] 0.5028145

Okay. So, worker $i$ if they are high types, they draw from $w_i \sim \mathcal{N}(3.62 , 0.50)$, with probability $P_{high} = 0.40$. On the other hand, low types draw their wages from $w_i \sim \mathcal{N}(2.63 , 0.50)$, with $P_{low} = 0.60$.

We can formally write this mixture as:

\[f(w_i; \mu, \sigma, \pi) = \sum^2_{m = 1} \pi_k N_k(w_i; \mu_k, \sigma_k, \pi_k)\]Where $f_k(w_i; \mu_k, \sigma_k, \pi_k)$ represents the pdf of a particular Gaussian distribution from the mixture.

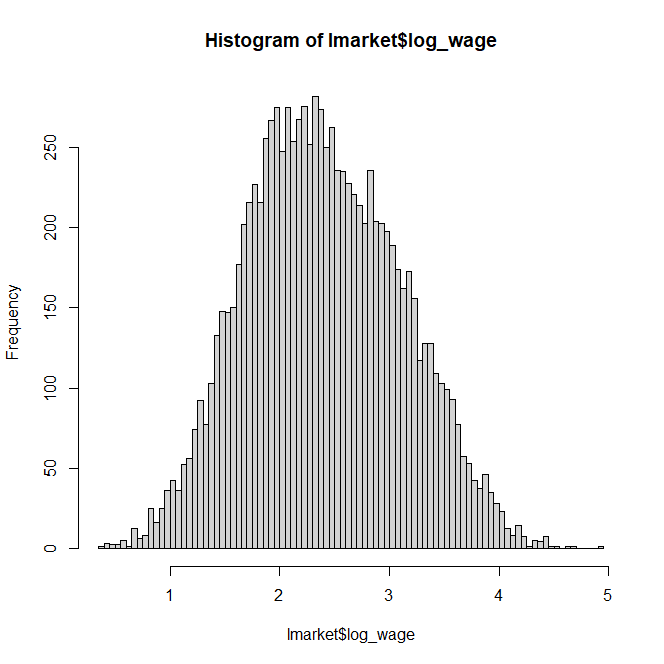

Let’s plot the histogram of worker log-wages:

X11()

hist(lmarket$log_wage, breaks = 100)

Notice how we can barely see the mixture components in this histogram. In real-world data, wages are all over the place the same way this plot shows. However, if we are to believe a particular human capital amount has a direct effect on potential income, it is hard to conclude all workers are drawing from a single distribution function. There must be “hidden” distributions blended together. So how do we extract them?

The first step is to guess the initial moments and priors. For the guess, we can use a simple k-means routine to slice the data. Since we know this mixture has two components, we slice the data in 2 parts.

# Guess the initial parameters

initial_guess <- kmeans(lmarket$log_wage,2)$cluster

mu1 <- mean(lmarket$log_wage[initial_guess==1])

mu2 <- mean(lmarket$log_wage[initial_guess==2])

sigma1 <- sd(lmarket$log_wage[initial_guess==1])

sigma2 <- sd(lmarket$log_wage[initial_guess==2])

pi1 <- sum(initial_guess==1)/length(initial_guess)

pi2 <- sum(initial_guess==2)/length(initial_guess)

Here I created the parameters for each component assuming the kmeans did the “right guess”.

We need to find the expected value of the log likelihood of these parameters.

$\mathcal{L} = \sum_i \sum_k [\log \pi_k + \log f_k(w_i; \mu_k, \sigma_k, \pi_k)]$

Now, let us create a variable that will store the log-likelihood function output.

# modified sum only considers finite values

sum_finite <- function(x) {

sum(x[is.finite(x)])

}

L <- 0

I also created an auxiliar function to bypass values dangerously close to zero inside logs, since we will deal with a lot of logs from now on, as you can see below:

# starting value of expected value of the log likelihood

L[2] <- sum_finite(log(pi1)+log(dnorm(lmarket$log_wage, mu1, sigma1))) + sum_finite(log(pi2)+log(dnorm(lmarket$log_wage, mu2, sigma2)))

$L$ is an array that will store the log-likelihood outputs. We just calculated the expected log likelihood of this mixture given the guess.

We are ready to start the “Expectation” part of the EM algorithm. Now we need to update the parameters and repeat until it converges. The rest of the routine is “simple”:

current_iter <- 2

while (abs(L[current_iter]-L[current_iter-1])>=1e-8) {

# E step

comp1 <- pi1 * dnorm(lmarket$log_wage, mu1, sigma1)

comp2 <- pi2 * dnorm(lmarket$log_wage, mu2, sigma2)

comp_sum <- comp1 + comp2

p1 <- comp1/comp_sum

p2 <- comp2/comp_sum

# M step

pi1 <- sum_finite(p1) / length(lmarket$log_wage)

pi2 <- sum_finite(p2) / length(lmarket$log_wage)

mu1 <- sum_finite(p1 * lmarket$log_wage) / sum_finite(p1)

mu2 <- sum_finite(p2 * lmarket$log_wage) / sum_finite(p2)

sigma1 <- sqrt(sum_finite(p1 * (lmarket$log_wage-mu1)^2) / sum_finite(p1))

sigma2 <- sqrt(sum_finite(p2 * (lmarket$log_wage-mu2)^2) / sum_finite(p2))

p1 <- pi1

p2 <- pi2

current_iter <- current_iter + 1

L[current_iter] <- sum(log(comp_sum))

}

In the Expectation Step, we’re computing the likelihood of each data point under each Gaussian component, weighted by their prior probabilities (pi1 and pi2). Then, we normalize these to get posterior probabilities (p1 and p2) for each data point.

In the Maximization step, we use these new posterior probabilities to update the mixing proportions. Then, we update the means and standard deviations and recalculate the log likelihood. We keep doing it until the difference between the previous result and the current result is sufficiently small.

Check out the results:

r$> mu1

[1] 3.64748

r$> sigma1

[1] 0.5000334

r$> pi1

[1] 0.3765109

r$> mu2

[1] 2.65694

r$> sigma2

[1] 0.5069525

r$> pi2

[1] 0.6234891

Not bad at all! But wait, how do we know how many mixture components there are? This is a very important question. Asssuming too few components will group together observations that are in fact distinct. Too many, and similar observations will end up in different components.

What happens if we assume 3 worker types instead of 2, for instance? We can quickly add another set of parameters and see what happens:

r$> mu1

[1] 1.794064

r$> mu2

[1] 2.638425

r$> mu3

[1] 3.599803

r$> sigma1

[1] 0.2860714

r$> sigma2

[1] 0.4679375

r$> sigma3

[1] 0.5121838

r$> pi1

[1] 0.01752382

r$> pi2

[1] 0.559895

r$> pi3

[1] 0.4225811

Well, that is not that bad. Look how component 2 and 3 are still very close to the true parameters. But now we have this weird component 1 that should not be there. That is fine though, only 1.7 percent of the data belongs to this component, meaning the algorithm probably had a hard time fitting it anyway.

So how to choose the most appropriate number of worker types if you ever come across a large dataset and you are willing to investigate worker and firm effects on wages? Well, testing and testing is the answer. Test multiple settings, observe the patterns. Are we far away of proper economic theory? Is it parsimonous enough to provide good intuition? There is no right or wrong, but good practice.